Art History Volume One Stokstad and Michael Cothren Pdf 6th Edition

Cerise dots: the iii main schools of Gupta art were located in Mathura, Varanasi and Nalanda.[i] White dots: secondary or peripheral locations.

Gupta art is the art of the Gupta Empire, which ruled virtually of northern India, with its height betwixt most 300 and 480 CE, surviving in much reduced form until c. 550. The Gupta period is generally regarded every bit a classic peak and aureate age of North Indian art for all the major religious groups.[two] Gupta art is characterized by its "Classical decorum", in dissimilarity to the subsequent Indian medieval art, which "subordinated the figure to the larger religious purpose".[3]

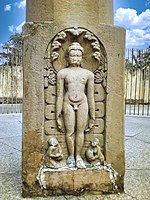

Although painting was evidently widespread, the surviving works are almost all religious sculpture. The period saw the emergence of the iconic carved rock deity in Hindu art, while the production of the Buddha-effigy and Jain tirthankara figures continued to expand, the latter ofttimes on a very large scale. The traditional main centre of sculpture was Mathura, which continued to flourish, with the fine art of Gandhara, the centre of Greco-Buddhist fine art simply beyond the northern border of Gupta territory, continuing to exert influence. Other centres emerged during the period, particularly at Sarnath. Both Mathura and Sarnath exported sculpture to other parts of northern India.

Information technology is customary to include under "Gupta art" works from areas in north and central Bharat that were not actually nether Gupta command, in particular fine art produced under the Vakataka dynasty who ruled the Deccan c. 250–500.[4] Their region contained very important sites such every bit the Ajanta Caves and Elephanta Caves, both mostly created in this period, and the Ellora Caves which were probably begun and so. Also, although the empire lost its western territories by about 500, the artistic style connected to exist used across well-nigh of northern India until about 550,[v] and arguably around 650.[half-dozen] It was then followed past the "Postal service-Gupta" menstruum, with (to a reducing extent over time) many like characteristics; Harle ends this around 950.[seven]

In general the mode was very consistent across the empire and the other kingdoms where it was used.[eight] The vast majority of surviving works are religious sculpture, mostly in stone with some in metal or terra cotta, and compages, by and large in stone with some in brick. The Ajanta Caves are nigh the sole survival from what was apparently a large and sophisticated body of painting,[ix] and the very fine coinage the primary survivals in metalwork. Gupta India produced both textiles and jewellery, which are only known from representations in sculpture and especially the paintings at Ajanta.[10]

Groundwork [edit]

Gupta art was preceded by Kushan art, the art of the Kushan Empire in northern India, which flourished betwixt the 1st and the 4th century CE and blended the tradition of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, influenced by Hellenistic creative canons, and the more than Indian fine art of Mathura.[11] In Western India, every bit visible in Devnimori, the Western Satraps (1st–fourth century CE) adult a refined art, representing a Western Indian artistic tradition that was inductive to the rising of Gupta fine art, and which may have influenced not but the latter, but also the fine art of the Ajanta Caves, Sarnath and other places from the 5th century onward.[12] [xiii] [fourteen] In primal India, the fine art of the Satavahanas had already created a rich Indian artistic idiom, equally visible in Sanchi, which also influenced Gupta art.[xiv]

With the conquests of Samudragupta (r.c. 335/350-375 CE) and Chandragupta Two (r.c. 380 – c. 415 CE), the Gupta Empire came to incorporate vast portions of cardinal, northern and northwestern Republic of india, as far as the Punjab and the Arabian sea, standing and expanding on these earlier artistic traditions and developing a unique Gupta way, rising "to heights of sophistication, elegance and glory".[sixteen] [17] [eighteen] [19] Unlike some other Indian dynasties before and after them, and with the exception of the imagery on their coins, the Gupta imperial family did non advertise their relationship to the art produced nether them by inscriptions, let lone portraits that have survived.[20]

Early chronology [edit]

There are several pieces of statuary from the Gupta menstruation which are inscribed with a date.[21] They work as a benchmark for the chronology and the development of style under the Guptas. These Gupta statues are dated from the Gupta era (which starts in 318–319 CE), and sometimes mention the reigning ruler of that time.[21] Too bronze, coinage is also an important chronological indicator.[22]

Although the Gupta Empire is reckoned to starting time after King Gupta in the belatedly third century CE, the earliest known and dated sculptures of Gupta art come relatively late, nigh a century afterwards, after the conquest of northwestern India nether Samudragupta. Among the primeval is an inscribed pillar recording the installation of two Shiva Lingas in Mathura in 380 CE under Chandragupta II, Samudragupta'due south successor.[23] Some other rare example is a statue of a seated Bodhisattva in the Mathura style with dhoti and shawl on the left shoulder, coming from Bodh Gaya and dated to "twelvemonth 64", presumably of the Gupta era, idea to be 384 CE.[15] This type remained a rare occurrence, as in most of the after Gupta statues the Buddha would be shown with the samghati monastic robe covering both shoulders.[fifteen]

Coinage as well was a relatively tardily development, also consecutive to Samugragupta's conquest of the northwest.[24] [25] [26] The Gupta coinage was initially in imitation of the Kushan types.[27] [28] [29]

Manner [edit]

The Gupta style of bronze, especially as seen in the Buddha images, is characterized by several determinative traits: ornate halos with floral and gem motifs, wearing apparel with thin, diaphanous, curtain, specific hair curls, meditative eyes, elongated earlobes, relatively thick lower lips, and often three lines across the cervix.[30]

Sculpture [edit]

Iii chief schools of Gupta sculpture are often recognised, based in Mathura, Varanasi/Sarnath[31] and to a lesser extent Nalanda.[32] The distinctively dissimilar stones used for sculptures exported from the main centres described below aids identification greatly.[33]

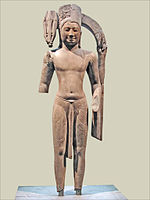

Both Buddhist and Hindu sculpture concentrate on big, often almost life-size, figures of the major deities, respectively Buddha, Vishnu and Shiva. The dynasty had a partiality to Vishnu, who now features more prominently, where the Kushan imperial family generally had preferred Shiva. Minor figures such equally yakshi, which had been very prominent in preceding periods, are at present smaller and less frequently represented, and the crowded scenes illustrating Jataka tales of the Buddha'south previous lives are rare.[34] When scenes include one of the major figures and other less important ones, at that place is a great difference in calibration, with the major figures many times larger. This is also the case in representations of incidents from the Buddha's life, which before had showed all the figures on the same scale.[35]

The lingam was the central murti in nearly temples. Some new figures appear, including personifications of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, not nevertheless worshipped, just placed on either side of entrances; these were "the two slap-up rivers encompassing the Gupta heartland".[36] The principal bodhisattva announced prominently in sculpture for the first fourth dimension,[37] as in the paintings at Ajanta. Buddhist, Hindu and Jain sculpture all testify the same fashion,[38] and there is a "growing likeness of form" betwixt figures from the different religions, which continued later on the Gupta period.[5]

The Indian stylistic tradition of representing the body as a serial of "shine, very simplified planes" is continued, though poses, particularly in the many standing figures, are subtly tilted and varied, in contrast to the "columnar rigidity" of earlier figures.[39] The particular of facial parts, hair, headgear, jewellery and the haloes behind figures are carved very precisely, giving a pleasing dissimilarity with the emphasis on broad swelling masses in the trunk.[xl] Deities of all the religions are shown in a calm and majestic meditative style; "perhaps information technology is this all-pervading inwardness that accounts for the unequalled Gupta and post-Gupta ability to communicate college spiritual states".[5]

Mathura school [edit]

The long-established Mathura school continued every bit one of the main two schools of Gupta Empire art, joined past the school of Varanasi and nearby Sarnath.[ane] Mathura sculpture is characterized by its usage of mottled carmine stone from Karri in the district, and its strange influences, continuing the traditions of the art of Gandhara and the art of the Kushans.[41]

The art of Mathura continued to get more sophisticated during the Gupta Empire. The pinkish sandstone sculptures of Mathura evolved during the Gupta menses to attain a very high fineness of execution and delicacy in the modeling, displaying calm and quiet. The manner become elegant and refined, with a very delicate rendering of the draping and a sort of radiance reinforced by the usage of pinkish sandstone.[1] Artistic details tend to be less realistic, as seen in the symbolic shell-like curls used to render the hairstyle of the Buddha, and the orante halos around the head of the Buddhas. The art of the Gupta is often considered as the pinnacle of Indian Buddhist art, achieving a beautiful rendering of the Buddhist platonic.[1]

Gupta art is also characterized past an expansion of the Buddhist pantheon, with a high importance given to the Buddha himself and to new deities, including Bodhisattvas such as Avalokitesvara or divinities of Bramanical inspiration, and less focus on the events of the life of the Buddha which were abundantly illustrated through Jataka stories in the art of Bharhut and Sanchi (2nd–1st centuries BCE), or in the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara (1st–fourth centuries CE).[42]

The Gupta fine art of Mathura was very influential throughout northern India, accompanied by a reducing of foreign influences; its style tin can be seen in Gupta statues to the east in areas as far every bit Allahabad, with the Mankuwar Buddha, dated to the reign of Kumaragupta I in 448.[43]

There are a number of "problematical" Buddhist and Jain images from Mathura whose dating is uncertain; many are dated with a low year number, simply which era is beingness used is unclear. These may well come from the early on Gupta period.[v]

-

Buddha in Abhaya Mudra. Kushana-Gupta transitional period. Circa tertiary-4th century, Mathura.[44]

-

Standing Buddha, inscribed Gupta Era yr 115 (434 CE), Mathura.[45]

-

Caput of a Buddha, 6th century.

-

A relief of the Trivikrama , "three strides of Vishnu", in the fine art of Mathura during the Gupta catamenia.

-

Vishnu statue, fifth century, Mathura.

-

Seated Jain Tirthankara, circa fifth Century CE, Mathura.

Sarnath school [edit]

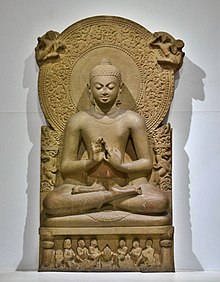

The Varanasi/ Sarnath style produced mainly Buddhist art, and "Sarnath Buddhas are probably the greatest single achievement of the Indian sculptor", largely setting the representation of the Buddha that was followed in eastern India and South-East Asia for many centuries, and the full general representation of the human body in India.[49] A number of dated examples show that the mature style did not develop until 450–475.[l] It is characterized by its yellowish sandstone from the quarries of Chunar, and lacks the foreign influences seen in Mathura.[42] Folds on clothing have disappeared, and the clothing itself is extremely thin, to the point of being transparent. The halo has get large and is often elaborately busy.[51] The top edge of the eye-socket is very marked, forming a sharply carved edge.[52]

The Sarnath style was the origin of Buddha images in Siam, Cambodia and Java.[53]

-

Buddha caput, Sarnath, 5th century

-

Buddha, 450-500

-

Other centres [edit]

- Nalanda

Gupta sculptural qualities tend to deteriorate with time, equally in Nalanda in Bihar in the sixth century BCE, figures become heavier and tend to exist made in metal. This evolution suggests a third schoolhouse of Gupta art in the area Nalanda and Pataliputra, too the two main centres of Mathura and Vanarasi. The colossal Sultanganj Buddha in copper from the area of Pataliputra is a uniquely big survival from this school, but typical in style.[42] In the same monastery two like but much smaller (and slightly later) figures in stone were plant, ane now on display in the British Museum.[57]

- Udayagiri Caves/Vidisha

The "first dated sculptures in a fully-fledged early Gupta fashion" come from the rock-cut Udayagiri Caves and the surrounding area nearly Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh.[58] Though the caves, all just one Hindu, are "of negligible importance architecturally", around the cave entrances are a number of rock relief panels, some with large deities. They are in a relatively crude and heavy style, but often with a powerful affect; Harle describes the mukhalinga in Cave 4 as "pulsating with psychic power". The most famous is the 7 10 4 metre relief of Vishnu in the form of the giant boar Varaha, raising the earth from the primordial waters, watched by rows of much smaller gods, sages and celestial beings. Ane cave also has an extremely rare inscription relating a site to the Gupta courtroom, recording the donation of a minister of Candragupta Ii.[59] The famous Fe pillar of Delhi is thought likely to take been originally gear up outside the caves.

-

Head of Vishnu from Vidisha well-nigh Udayagiri, Central India, 4th century

- Eran

Eran in Madhya Pradesh has a "pillar" or big single cavalcade dated 484/5 by an inscription of Buddhagupta, the just standing Gupta example, with 2 Garuda figures at the top (illustrated below). It had ii big Varaha figures outside the ruined Gupta temple. The manner of the sculpture is somewhat provincial. Still at the site is a huge and impressive boar on four legs, with no human characteristics, its torso covered with rows of small figures representing the sages who clung to the hairs of Varaha to save themselves from the waters. Now moved to the academy museum at Sagar is a figure with the same body and pose as that at Udayagiri, "one of the greatest of all Indian sculptures ... nothing can friction match the figure'due south air of insolent triumph". Both are dated to the late fifth century.[63]

- Others

The surviving sanctuary of the early 6th-century Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh has a typically fine doorway, and large relief panels on the other iii walls. These are now external, merely would originally gave given on to the covered convalescent. Though "regal", these show "the sturdiness of early Gupta sculpture is yielding to a softer, more delicate and ultimately weaker style".[64] The row of men beneath the sleeping Vishnu have "stylized poses, probably imitated from the theatre".[65]

At that place are also other small centres of Gupta sculpture, specially in the areas of Dasapura and Mandasor, where a huge 8-faced mukhalinga (probably early on 6th-century) found in the river has been reinstalled in the Pashupatinath Temple, Mandsaur.[66]

The Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara continued a belatedly phase through at to the lowest degree near of the Gupta catamenia, having also been a formative influence.[58]

Very of import rock-cut sites outside the Gupta Empire proper, to the south, are the Ajanta Caves and Elephanta Caves, both mostly created in the Gupta period, and the Ellora Caves which were probably begun around the stop of it. Every bit it was mainly restricted to the Gangetic obviously, the vast Gupta territories included relatively few rock-cut sites with much sculpture. The afterward Ajanta manner of sculpture is somewhat heavy, but sometimes "awe-inspiring" in the big seated shrine Buddhas, but other smaller figures are often very fine, as is the ornamental etching on columns and door-frames.[67]

When combined with the painted walls, the result tin can be considered over-decorated, and lacking "motifs on a larger calibration to serve as focal points". The main internal carving was probably completed by 478, though votive figures to the sides of many cave entrances may exist later. The Ajanta way is only seen at a few other sites nearby. After work ended there much of the skilled workforce, or their descendants, probably concluded upwardly working at Elephanta and and then Ellora.[68]

Different the serial of caves side past side at Ajanta, the chief interest at Elephanta is the largest cave, a huge Shiva temple, and above all the colossal triple-bust (trimurti) of Shiva, 18 feet (5.five m) alpine, which "considering it is then amazingly skilfully placed in relation to the various external entrances ... receives exactly the amount of lite necessary to make it look as if it is emerging from a black void, manifestation from the unmanifest".[69] Also from the Bombay area, the Parel Relief or (Parel Shiva) is an important late Gupta monolithic relief of Shiva in seven forms.[70]

-

Vishnu, Central India, fifth century

-

-

Mother Goddess from entrance of a Hindu Temple, Tanesara-Mahadeva (near Udaipur), suggesting connections with the Art of Gandhara.[71] 5th-6th[72] [73] or early 7th century CE.[74]

-

Terra cotta sculpture [edit]

The primeval terracottas datable to the Gupta menstruum appear under the Western Satraps at the Buddhist site of Devnimori in Gujarat circa 375–400 CE, representing the southern extension of Gandharan influence to the subcontinent, which persisted locally with the sites of Mīrpur Khās, Śāmalājī or Dhānk, a century before this influence would further extend to Ajanta and Sarnath.[75] [76] It has fifty-fifty been suggested that the fine art of the Western Satraps and Devnimori were at the origin of Gupta material culture, only this remains a subject of debate.[77]

The Gupta period saw the production of many sculptures in terracotta of very fine quality, and they are similar in style across the empire, to an even greater extent than the stone sculpture.[5] Some can still be seen in their original settings on the brick temple at Bhitargaon, where the large relief panels accept near worn abroad, but various heads and figures survive at higher levels.[78] The very elegant pair of river goddesses excavated from a temple at Ahichchhatra are 1.47 metres high.

Sculpture in metal [edit]

The over life-size copper Sultanganj Buddha (2.3 metres tall) is "the merely remaining metal statue of whatever size" from the Gupta menses, out of what was at the time probably approximately as numerous a type as stone or stucco statues.[81] In that location are, all the same, many much smaller near-identical figures (up to most fifty cm tall), several in American museums. The metal Brahma from Mirpur-Khas is older, but nigh one-half the size of the Sultanganj figure. The Jain Akota bronzes and some other finds are much smaller still, probably figures for shrines in well-off homes.[82]

The style of the Sultanganj effigy, made by lost-wax casting, is comparable to slightly before stone Buddha figures from Sarnath in "the smoothly rounded attenuation of body and limbs" and the very sparse, clinging trunk garment, indicated in the lightest of ways. The figure has "a feeling of animation imparted by the unbalanced opinion and the movement suggested by the sweeping silhouette of the enveloping robe".[81]

Coins and metalwork [edit]

Survivals of busy secular metalwork are very rare,[83] only a silvery plate in the Cleveland Museum of Art shows a crowded festival scene in rather worn relief.[84] There is too a highly decorated object in bronzed fe that is idea to exist a weight for an architect's "plummet" or measuring line, now in the British Museum.[85]

The gold coinage of the Guptas, with its many types and space varieties and its inscriptions in Sanskrit, are regarded equally the finest coins in a purely Indian style.[86] The Gupta Empire produced big numbers of gold coins depicting the Gupta kings performing diverse rituals, as well every bit silver coins clearly influenced by those of the earlier Western Satraps by Chandragupta Ii.[87]

Coinage [edit]

Gupta coinage but started with the reign of Samudragupta (335/350-375 CE), or possibly at the end of the reign of his begetter Chandragupta I, for whom only one money blazon in his proper name is known ("Chandragupta I and his queen"), probably a commemorative result minted by his son.[88] [25] [26] [89] The coinage of the Gupta Empire was initially derived from the coinage of the Kushan Empire, adopting its weight standard, techniques and designs, post-obit the conquests of Samudragupta in the northwest.[25] [26] [90] The Guptas even adopted from the Kushans the name of Dinara for their coinage, which ultimately came from the Roman name Denarius aureus.[91] [92] [93] The imagery on Gupta coins was initially derived from Kushan types, but the features before long became more Indian in both manner and field of study matter compared to earlier dynasties, where Greco-Roman and Western farsi styles were mostly followed.[94] [95] [96]

Silver plate with a festival scene

The usual layout is an obverse with a portrait of the king that is usually total-length, whether standing, seated or riding a horse, and on the contrary a goddess, near often seated on a throne. Oftentimes the king is sacrificing. The choice of images tin have political meaning, referring to conquests and local tastes; the types often vary betwixt parts of the empire.[97]

Types showing the male monarch hunting and killing diverse animals: lions (the "lion-slayer" type), tigers and rhinoceros very probable refer to new conquests in the areas where those animals were even so found. They may as well reflect influence from Sassanian silverware from Persia.[98] The rex standing and property a bow to one side (the "archer" blazon) was used by at to the lowest degree 8 kings; it may have been intended to associate the king with Rama. Profile heads of the rex are used on some silver coins for Western provinces added to the empire.[99]

Some gold coins commemorate the Vedic Ashvamedha equus caballus cede ritual, which the Gupta kings practised; these have the sacrificial equus caballus on the obverse and the queen on the reverse.[100] Samudragupta is shown playing a string musical instrument, wearing huge earrings, merely just a unproblematic dhoti. The only type produced nether Chandragupta I shows him and his queen standing next. The bird Garuda, bearer of Vishnu, is used as a symbol of the dynasty on many argent coins.[101] Some of these were in the past misidentified every bit fire altars.[102]

The silver coinage of the Guptas was made in faux of the coinage of the Western Satraps following their overthrow by Chandragupta II, inserting the Gupta peacock symbol on the opposite but retaining traces of the Greek fable and the ruler's portrait on the obverse.[103] [104] Kumaragupta and Skandagupta continued with the old type of coins (the Garuda and the Peacock types) and also introduced some other new types.[86] The copper coinage was more often than not confined to the era of Chandragupta Two and was more than original in design. Eight out of the nine types known to accept been struck by him have a effigy of Garuda and the name of the rex on it. The gradual deterioration in pattern and execution of the gold coins and the disappearance of silver money, behave ample evidence to their curtailed territory.[86]

-

Samudragupta (left) playing a instrument; Goddess, right, c 335-380

-

Samudragupta money with Ashvamedha horse standing in front of a yūpa sacrificial mail, with legend "The King of Kings, who had performed the Ashvamedha sacrifice, wins heaven later conquering the earth".[105] [106]

-

The queen, opposite of final, is holding a chowrie for the fanning of the horse and a needle-like pointed musical instrument, with fable "One powerful plenty to perform the Ashvamedha sacrifice".[105] [106]

-

Compages [edit]

Hindu temple of Bhitargaon, late 5th century, but considerably restored.[110].

For reasons that are not entirely articulate, for the most part the Gupta period represented a hiatus in Indian stone-cut architecture, with the first moving ridge of construction finishing before the empire was assembled, and the 2d wave kickoff in the late fifth century, only equally information technology was ending. This is the case, for example, at the Ajanta Caves, with an early group made by 220 CE at the latest, and a later one probably all later on well-nigh 460.[111] Instead, the period has left almost the first surviving gratis-standing structures in India, in particular the beginnings of Hindu temple architecture. As Milo Beach puts it: "Nether the Guptas, India was quick to join the rest of the medieval world in a passion for housing precious objects in stylized architectural frameworks",[112] the "precious objects" being primarily the icons of gods.

The almost famous remaining monuments in a broadly Gupta style, the caves at Ajanta, Elephanta, and Ellora (respectively Buddhist, Hindu, and mixed including Jain) were in fact produced under other dynasties in Central Republic of india, and in the instance of Ellora after the Gupta period, simply primarily reflect the monumentality and balance of Guptan style. Ajanta contains past far the most significant survivals of painting from this and the surrounding periods, showing a mature grade which had probably had a long development, mainly in painting palaces.[113] The Hindu Udayagiri Caves actually tape connections with the dynasty and its ministers,[114] and the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh is a major temple, ane of the primeval to survive, with important sculpture, although information technology has lost its mandapa and covered ambulatory for parikrama.[115]

Examples of early N Indian Hindu temples that take survived after the Udayagiri Caves in Madhya Pradesh include those at Tigawa (early 5th century),[116] Sanchi Temple 17 (similar, but respectively Hindu and Buddhist), Deogarh, Parvati Temple, Nachna (465),[117] Bhitargaon, the largest Gupta brick temple to survive,[118] and Lakshman Brick Temple, Sirpur (600–625 CE). Gop Temple in Gujarat (c. 550 or subsequently) is an oddity, with no surviving close comparator.[119]

At that place are a number of unlike broad models, which would continue to be the case for more than a century later on the Gupta catamenia, merely temples such equally Tigawa and Sanchi Temple 17, which are small-scale but massively congenital stone prostyle buildings with a sanctuary and a columned porch, testify the virtually mutual basic program that is elaborated in after temples to the nowadays day. Both of these accept apartment roofs over the sanctuary, which would become uncommon by about the eighth century. The Mahabodhi Temple, Bhitargaon, Deogarh and Gop already all show high superstructures of different shapes.[120] The Chejarla Kapoteswara temple demonstrates that free-continuing chaitya-hall temples with barrel roofs connected to be built, probably with many smaller examples in wood.[121]

-

The current structure of the Mahabodhi Temple dates to the Gupta era, 5th century. Marking the location where the Buddha is said to have attained enlightenment.

-

Vishnu temple in Eran, late 5th century.

Pillars [edit]

Pillars with inscriptions were erected, recording the main achievements of Gupta rulers. Whereas the Pillars of Ashoka were cylindrical, smoothen and finished with the famous Mauryan smooth, Gupta pillars had a rough surface often shaped into geometrical facets.[122]

Painting [edit]

Ajanta cavern 17, frescoes higher up a lintel

Painting was obviously a major art in Gupta times, and the varied paintings of the Ajanta Caves, which are much the best survivals (nearly the but ones), show a very mature style and technique, conspicuously the effect of a well-adult tradition.[123] Indeed, it is recorded that skill in amateur painting, especially portraits, was considered a desirable accomplishment among Gupta elites, including royalty. Ajanta was ruled by the powerful Vakataka dynasty, beyond the territory of the Gupta Empire, simply it is thought to closely reflect the metropolitan Gupta mode.[124] The other survivals are from the Bagh Caves, now more often than not removed to the Gujari Mahal Archaeological Museum in Gwalior Fort, Ellora, and Cave Three of the Badami cave temples.[125]

At Ajanta, it is thought that established teams of painters, used to decorating palaces and temples elsewhere, were brought in when required to decorate a cave. Mural paintings survive from both the earlier and later groups of the caves. Several fragments of murals preserved from the earlier caves (Caves ten and 11) are effectively unique survivals of ancient painting in India from this period, and "show that by Sātavāhana times, if non before, the Indian painters had mastered an easy and fluent naturalistic style, dealing with large groups of people in a manner comparable to the reliefs of the Sāñcī toraņa crossbars".[126]

Four of the afterward caves have large and relatively well-preserved mural paintings which "take come to stand for Indian mural painting to the non-specialist",[126] and correspond "the peachy glories not just of Gupta but of all Indian art".[127] They fall into two stylistic groups, with the most famous in Caves 16 and 17, and what used to thought of as afterward paintings in Caves 1 and 2. Withal, the widely accepted new chronology proposed by Spink places both groups in the 5th century, probably before 478.[128]

The paintings are in "dry fresco", painted on top of a dry out plaster surface rather than into wet plaster.[129] All the paintings appear to be the work of painters supported by discriminating connoisseurship and sophisticated patrons from an urban atmosphere. Unlike much Indian mural painting, compositions are not laid out in horizontal bands similar a frieze, just prove large scenes spreading in all directions from a single figure or grouping at the centre.[130] The ceilings are besides painted with sophisticated and elaborate decorative motifs, many derived from sculpture.[131] The paintings in cave 1, which according to Spink was commissioned by Harisena himself, concentrate on those Jataka tales which show previous lives of the Buddha equally a king, rather than as a deer or elephant or other animal.[132] The Ajanta paintings have seriously deteriorated since they were rediscovered in 1819, and are now mostly difficult to appreciate at the site. A number of early attempts to re-create them met with misfortune.

But mural paintings survive, but it is clear from literary sources that portable paintings, including portraits, were mutual, probably including illustrated manuscripts.[129]

- Cave 1 at Ajanta

-

One of four frescos for the Mahajanaka Jataka tale. The king announces he abdicates to become an ascetic.[133]

-

Sibi Jataka: king undergoes the traditional rituals for renouncers. He receives a ceremonial bath.[134] [135]

-

Chronology [edit]

The chronology of Gupta art is quite critical to the fine art history of the region. Fortunately, several statues are precisely dated, based on inscriptions referring to the various rulers of the Gupta Empire, and giving their regnal dates in the Gupta era.

Concluding period: Sondani (525 CE) [edit]

The sculptures at Sondani and surrounding areas of Mandsaur are a proficient marker for the terminal catamenia of Gupta Art, as they were commissionned past Yasodharman (ruled 515 – 545 CE) around 525 CE, in celebration of his victory against the Alchon Hun rex Mihirakula.[146] [147] This corresponds to the last phase of Gupta cultural and political unity in the subcontinent, and later that point and for the next centuries, Indian politics became extremely fragmented, with the territory being divided between smaller dynasties.[148] The art of Sondani is considered as transitional betwixt Gupta art and the art of Medieval India: it represents "an aesthetic which hovered betwixt the classical decorum of Gupta art on the 1 paw and on the other the medieval canons which subordinated the figure to the larger religious purpose".[149]

-

Sondani pillar upper-case letter, circa 525 CE

-

-

Influences in Southeast Asia [edit]

Central Thailand, Dvaravati, Mon-Dvaravati style, 7th–9th Century.

Indian art, peculiarly Gupta and Post-Gupta fine art from Eastern India, was influential in the evolution of Buddhist and Hindu fine art in Southeast Asia from the 6th century CE.[150] The Mon people of the kingdom of Dvaravati in modern Thailand were among the start to prefer Buddhism, and adult a item manner of Buddhist fine art. Mon-Davarati statues of the Buddha take facial features and hair styles reminiscent of the fine art of Mathura.[150] In pre-Angkorian Cambodia from the 7th century CE, Harihara statues fusing the characteristics of Shiva and Vishnu are known.[150]

-

A seated Buddha in Dvaravati style, 6th century CE

-

Harihara statue, Kingdom of cambodia, seventh century CE

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d Mookerji, 142

- ^ Rowland's chapter 15 is called "The Gilt Age: The Gupta Menstruation; Harle, 88

- ^ Williams, Joanna (1972). "The Sculpture of Mandasor" (PDF). Archives of Asian Art. 26: 64. ISSN 0066-6637.

- ^ Harle, 118

- ^ a b c d e Harle, 89

- ^ Rowland, 215

- ^ Harle, 199

- ^ Harle, 89; Rowland, 216

- ^ Harle, 88, 355–361

- ^ Rowland, 252–253

- ^ Stokstad, Marilyn; Cothren, Michael W. (2013). Fine art History (5th Edition) Chapter ten: Art Of South And Southeast Asia Earlier 1200. Pearson. pp. 306–308. ISBN978-0205873487.

- ^ Schastok, Sara L. (1985). The Śāmalājī Sculptures and sixth Century Art in Western Republic of india. BRILL. pp. 23–31. ISBN978-9004069411.

- ^ a b c The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Book 4 1981 Number I An Exceptional Group of Painted Buddha Figures at Ajanṭā, p.97 and Note 2

- ^ a b "Gupta art in north Bharat of the 5th century did receive the heritage of the Mathura as well as Ksatrapa-Satavahana arts." in Pal, Pratapaditya (1972). Aspects of Indian Art: Papers Presented in a Symposium at the Los Angeles County Museum of Fine art, October, 1970. Brill Archive. p. 47. ISBN9789004036253.

- ^ a b c d Rhi, Ju-Hyung (1994). "From Bodhisattva to Buddha: The Beginning of Iconic Representation in Buddhist Art". Artibus Asiae. 54 (3/4): 223. doi:10.2307/3250056. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3250056.

- ^ Duiker, William J.; Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2015). World History. Cengage Learning. p. 279. ISBN9781305537781.

- ^ Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 143. ISBN9788120804401.

- ^ Gokhale, Balkrishna Govind (1995). Ancient India: History and Civilization. Pop Prakashan. pp. 171–173. ISBN9788171546947.

- ^ Lowenstein, Tom (2012). The Culture of Ancient India and Southeast Asia. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 53. ISBN9781448885077.

- ^ Harle, 88

- ^ a b Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 98–100. ISBN978-81-208-0592-vii.

- ^ Pal, 69

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ Altekar, A. s (1957). Coinage Of The Gupta Empire. p. 39.

- ^ a b c Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 30. ISBN9788120804401.

- ^ a b c Higham, Charles (2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 82. ISBN9781438109961.

- ^ "Information technology was his conquests which brought to him the gilt utilized in his coinage and also the knowledge of its technique acquired from his acquaintance with Kushan (eastern Punjab) coins. His earliest coins began as imitations of these Kushan coins, and of their strange features which were gradually replaced by Indian features in his later coins." in Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 30. ISBN9788120804401.

- ^ Pal, 78

- ^ Art, Los Angeles Canton Museum of; Pal, Pratapaditya (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700 . University of California Press. p. 73. ISBN9780520059917.

- ^ Ishikawa, Ken (2019). "More Gandhāra than Mathurā: substantial and persistent Gandhāran influences provincialized in the Buddhist material culture of Gujarat and beyond, c. AD 400–550" in "The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art". p. 166.

"However, all the Gupta Buddha images show one or more formative-Gupta characteristics: the ornament of the halo with floral and gem motifs, the garments with diaphanous pall, hair curls, meditative optics, elongated earlobes, the pronounced lower lip and/or three lines beyond his neck (Miyaji 1980: sixteen).

- ^ Asher, Frederick Grand. (2003), "Sarnath", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Printing, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t076054, ISBN978-1-884446-05-4 , retrieved 2020-12-25

- ^ Mookerji, ane, 143

- ^ Harle, 89; Rowland, 216; Mookerji, 143

- ^ Harle, 87–88

- ^ Rowland, 234

- ^ Harle, 87–88, 88 quoted

- ^ Rowland, 235

- ^ Rowland, 232

- ^ Rowland, 233

- ^ Rowland, 230–233, 232 and 233 quoted

- ^ Rowland, 229–232; Mookerji, 143

- ^ a b c d eastward Mookerji, 143

- ^ Mookerji, 142–143

- ^ "Kushana-Gupta transitional period" per Mathura Museum label, visible on the photograph.

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ For English summary, run into page eighty Schmid, Charlotte (1997). Les Vaikuṇṭha gupta de Mathura : Viṣṇu ou Kṛṣṇa?. pp. 60–88.

- ^ Rowland, 234–235; Harle, 109–110

- ^ Harle, James C. (January 1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 109. ISBN978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ Harle, 107–110, 107 quoted

- ^ Harle, 110

- ^ Rowland, 232–237;

- ^ Harle, 89–90

- ^ Harle, 109–110; Rowland, 235

- ^ Fleet, John Faithfull (1960). Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors. p. 47.

- ^ "Mankuwar Buddha Image Inscription of the Time of Kumaragupta I siddham". siddham.uk.

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ British Museum page [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ a b Harle, 92

- ^ Harle, 92–97, 93 quoted

- ^ Harle, 93

- ^ Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (28 November 2016). Not bad Events in Organized religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 271. ISBN978-1-61069-566-4.

- ^ BECKER, CATHERINE (2010). "Not Your Average Boar: The Jumbo Varāha at Erāṇ, an Iconographic Innovation". Artibus Asiae. seventy (1): 127. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 20801634.

- ^ Harle, 97–100, 99–100 quoted

- ^ Harle, 113

- ^ Harle, 113–114

- ^ Mookerji, 144; Harle, 114

- ^ Harle, 118–120 (120 quoted), 122–124

- ^ Harle, 122

- ^ Harle, 124

- ^ Harle, 124

- ^ "Mother Goddess". Cleveland Museum of Art. 31 October 2018.

- ^ India, Rajasthan, Tanesara-Mahadeva, Gupta Period. "Matrika from Tanesara".

- ^ "Mother Goddess". Cleveland Museum of Fine art. 31 Oct 2018.

- ^ Harle, James C. (January 1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 115. ISBN978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ Ishikawa, Ken (2020). "More Gandhāra than Mathurā: substantial and persistent Gandhāran influences provincialized in the Buddhist textile civilization of Gujarat and beyond, c. AD 400–550" in "The Global Connections of Gandhāran Fine art" (PDF). Archaeopress Archaeology. pp. 156–157.

Furthermore, I will trace the waves of Gandhāran influences observed at Devnīmorī, which within, or afterward, a century or so somewhen reached Sārnāth and Ajaṇṭā and locally persisted at Śāmalājī in north Gujarat, Dhānk in Saurashtra in India, and Mīrpur Khās in Sindh in Pakistan.

- ^ Ishikawa, Ken. The Global Connections of Gandhāran Art. p. 168.

Overall, the early on Gupta Jain tīrthaṅkara images from Vidiśā are regarded equally anticipating, together with the Bodh Gayā Buddha/Bodhisattva image and fully-fledged Gupta-fashion buddha images at Devnīmorī shortly after, the fully-fledged/mature Gupta Buddha images at Mathurā and Sārnāth that developed during the following 5th century AD.

- ^ Ishikawa, Ken (2019). "More Gandhāra than Mathurā: substantial and persistent Gandhāran influences provincialized in the Buddhist fabric culture of Gujarat and beyond, c. Advertizing 400–550" in "The Global Connections of Gandhāran Fine art". pp. 156ff.

Notwithstanding, the thought that Devnīmorī or the Western Kṣatrapas were the progenitor of Gupta material civilization has long been a subject area of contend (Williams 1982 58-9). Although the role of western India in the formation of pan-Indian Gupta material culture is a notoriously problematic issue, we might farther contextualize Devnīmorī by reconsidering the extent of the late Gandhāran influence as well as pre-existing material civilization of Gujarat.

- ^ Harle, 115

- ^ Indian Art. Prince of Wales Museum of Western India. 1964. pp. 2–4.

The terracotta figures of Mirpur Khas represent the Gupta idiom as it flourished in Sindh. (...) In the terracottas of Mirpur Khas, of which the Museum has a nigh representative collection, i may see the synthesis of Gandhara and Gupta traditions . Here the old sacrosanct forms of Gandhara are moulded in the Gupta grapheme of nobility , restraint and spirituality and the result is very pleasing. The figures of the Buddha from Mirpur Khas show transformation from the Gandhara to Gupta idiom , which the figures of the donor and Kubera show well developed Gupta types.

- ^ Harle, James C. (January 1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale Academy Printing. p. 117. ISBN978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ a b Rowland, 237

- ^ Rowland, 237–239

- ^ Rowland, 253

- ^ "Plate with a Scene of Revelry", Cleveland Museum of Art

- ^ Rowland, 253–254

- ^ a b c The Coins Of India, by Brown, C.J. p.13-xx

- ^ Allan, J. & Stern, Southward. M. (2008), coin, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Altekar, A. s (1957). Coinage Of The Gupta Empire. p. 39.

- ^ Brown, C. J. (1987). The Coins of India. Asian Educational Services. p. 41. ISBN9788120603455.

- ^ Sen, Sudipta (2019). Ganges: The Many Pasts of an Indian River. Yale Academy Printing. p. 205. ISBN9780300119169.

- ^ "Known by the term Dinars in early Gupta inscriptions, their gold coinage was based on the weight standard of the Kushans i.e. 8 gms/120 grains. Information technology was replaced in the time of Skandagupta by a standard of lxxx ratis or 144 grains" Vanaja, R. (1983). Indian Coinage. National Museum.

- ^ Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 31. ISBN9788120804401.

- ^ Gupta inscriptions using the term "Dinara" for coin: No 5-nine, 62, 64 in Fleet, John Faithfull (1960). Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors.

- ^ "Information technology was his conquests which brought to him the aureate utilized in his coinage and too the cognition of its technique acquired from his acquaintance with Kushan (eastern Punjab) coins. His primeval coins began as imitations of these Kushan coins, and of their foreign features which were gradually replaced by Indian features in his subsequently coins." in Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997). The Gupta Empire. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. thirty. ISBN9788120804401.

- ^ Pal, 78

- ^ Art, Los Angeles County Museum of; Pal, Pratapaditya (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700 . University of California Printing. p. 73. ISBN9780520059917.

- ^ Mookerji, 139–141; Bajpai, 121; Pal, 78–lxxx

- ^ Sircar, 215–217; Pal, 74–75. The culling caption is that these animals were yet more widespread than is usually idea.

- ^ Mookerji, 139–141; Pal, 73–74

- ^ Glucklich, 111–113; Mookerji, 140; Pal, 79–lxxx suggests instead the female person effigy may correspond Vijaya, the goddess of victory.

- ^ Mookerji, 139–141; Pal, 73–75

- ^ Bajpai, 121–124

- ^ Prasanna Rao Bandela (2003). Coin splendour: a journey into the by. Abhinav Publications. pp. 112–. ISBN978-81-7017-427-1 . Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ "Evidence of the conquest of Saurastra during the reign of Chandragupta Two is to exist seen in his rare silver coins which are more than direct imitated from those of the Western Satraps... they retain some traces of the old inscriptions in Greek characters, while on the contrary, they substitute the Gupta type (a peacock) for the chaitya with crescent and star." in Rapson "A catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. The Andhras etc...", p. cli

- ^ a b Houben, January Due east. M.; Kooij, Karel Rijk van (1999). Violence Denied: Violence, Non-Violence and the Rationalization of Violence in S Asian Cultural History. BRILL. p. 128. ISBN978-xc-04-11344-2.

- ^ a b Ganguly, Dilip Kumar (1984). History and Historians in Ancient India . Abhinav Publications. p. 152. ISBN978-0-391-03250-vii.

- ^ "Evidence of the conquest of Saurastra during the reign of Chandragupta II is to exist seen in his rare silver coins which are more directly imitated from those of the Western Satraps... they retain some traces of the old inscriptions in Greek characters, while on the reverse, they substitute the Gupta type ... for the chaitya with crescent and star." in Rapson "A catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. The Andhras etc.", p.cli

- ^ Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (2016). Great Events in Organized religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 271. ISBN978-1-61069-566-4.

- ^ Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (28 November 2016). Neat Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [iii volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 271. ISBN978-ane-61069-566-4.

- ^ Harle, James C. (January 1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 116. ISBN978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ Ajanta chronology is yet nether discussion, but this is the view of Spink, accepted by many.

- ^ Beach, Milo, Steps to Water: The Ancient Stepwells of India, (Photographs by Morna Livingston), p. 25, 2002, Princeton Architectural Printing, ISBN 1568983247, 9781568983240, google books

- ^ J.C. Harle 1994, pp. 118–22, 123–26, 129–35. sfn error: no target: CITEREFJ.C._Harle1994 (help)

- ^ J.C. Harle 1994, pp. 92–97. sfn fault: no target: CITEREFJ.C._Harle1994 (help)

- ^ Harle, 113–114; come across besides site entries in Michell (1990)

- ^ Michell (1990), 192

- ^ Michael Meister (1987), Hindu Temple, in The Encyclopedia of Religion, editor: Mircea Eliade, Volume fourteen, Macmillan, ISBN 0-02-909850-5, page 370

- ^ Michell (1990), 157; Michell (1988), 96

- ^ Harle, 111–113, 136–138; Michell (1988), ninety, 96–98; run across as well site entries in Michell (1990)

- ^ Harle, 111–113; Michell (1988), 94–98

- ^ Harle, 175

- ^ "Gupta – artistes built it with the rough surface and with the different shapes of foursquare, octagonal and hexagonal. They decorated the pillars with the meandering creepers, flowers of blue and red lotuses, pitchers and the pattern of leogryph." Sudhi, Padma (1993). Gupta Art, a Study from Artful and Approved Norms. Milky way Publications. p. 120. ISBN978-81-7200-007-3.

- ^ Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (2005). A Earth History of Fine art. Laurence King Publishing. p. 244. ISBN978-1-85669-451-iii.

- ^ Harle, James C. (January 1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 118. ISBN978-0-300-06217-5.

- ^ Harle, 355, 361

- ^ a b Harle, 355

- ^ Harle, 356

- ^ Harle, 355–361; Spink

- ^ a b Harle, 361

- ^ Harle, 359

- ^ Harle, 355–361

- ^ Spink 2008

- ^ "Mahajanaka Jataka: Ajanta Cave 1". University of Minnesota.

- ^ a b c Benoy Behl (2004), Ajanta, the fountainhead, Frontline, Volume 21, Issue xx

- ^ Gupte & Mahajan 1962, pp. 32–33, Plate Xi.

- ^ Gupte & Mahajan 1962, pp. 8–9, Plate IV.

- ^ Spink 2009, pp. 138–140. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ Curta, Florin; Holt, Andrew (28 November 2016). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History [iii volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 271. ISBN978-ane-61069-566-iv.

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ Fleet, John Faithfull (1960). Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors. p. 47.

- ^ "Mankuwar Buddha Image Inscription of the Fourth dimension of Kumaragupta I siddham". siddham.uk.

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds". vmis.in. American Institute of Indian Studies.

- ^ Majumdar, B. (1937). Guide to Sarnath. p. 89.

- ^ Coin Cabinet of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

- ^ Williams, Joanna (1972). "The Sculpture of Mandasor" (PDF). Archives of Asian Fine art. 26: 63. ISSN 0066-6637.

- ^ "The reign of Yasodharman thus forms an important dividing point between the flow of the imperial Guptas, whom he emulated, and the following centuries, when India fell into a kaleidoscopic defoliation of shifting smaller dynasties" in Williams, Joanna (1972). "The Sculpture of Mandasor" (PDF). Athenaeum of Asian Art. 26: 52. ISSN 0066-6637.

- ^ Williams, Joanna (1972). "The Sculpture of Mandasor" (PDF). Archives of Asian Fine art. 26: 64. ISSN 0066-6637.

- ^ a b c Stokstad, Marilyn; Cothren, Michael W. (2013). Art History (5th Edition) Chapter 10: Art Of S And Southeast Asia Before 1200. Pearson. pp. 323–325. ISBN978-0205873487.

References [edit]

- Bajpai, Thousand. D., Indian Numismatic Studies, 2004, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 8170170354, 9788170170358, google books

- Glucklich, Ariel (2007). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN9780195314052.

- Gupte, Ramesh Shankar; Mahajan, B. D. (1962). Ajanta, Ellora and Aurangabad Caves. D. B. Taraporevala.

- Harle, J.C., The Fine art and Compages of the Indian Subcontinent, second edn. 1994, Yale Academy Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Mookerji, Radhakumud (1997), The Gupta Empire, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 9788120804401, google books

- Michell, George (1988), The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to its Significant and Forms, 2nd edn., Academy of Chicago Printing, ISBN 978-0-226-53230-i

- Michell, George (1990), The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of Bharat, Book 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, 1990, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445

- Rowland, Benjamin, The Fine art and Architecture of Republic of india: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1967 (third edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Pal, Pratapaditya, Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700, Volume 1 of Indian Sculpture: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Fine art Drove, 1986, Los Angeles Canton Museum of Fine art/University of California Press, ISBN 0520059913, 9780520059917, google books

- Sircar, D.C., Studies in Indian Coins, 2008, Motilal Banarsidass Publisher, 2008, ISBN 8120829735, 9788120829732, google books

- Spink, Walter Chiliad. (2008), Ajanta Lecture, Korea May 2008 (revised September 2008)

0 Response to "Art History Volume One Stokstad and Michael Cothren Pdf 6th Edition"

Post a Comment